Graffiti as Art!

Any passerby in an urban cityscape has observed the colorful, provocative, illegal "eyesore" that is graffiti. Although many consider the spray-painted pieces a nuisance, graffiti has been gaining recognition from the art world more and more as a legitimate form of art.

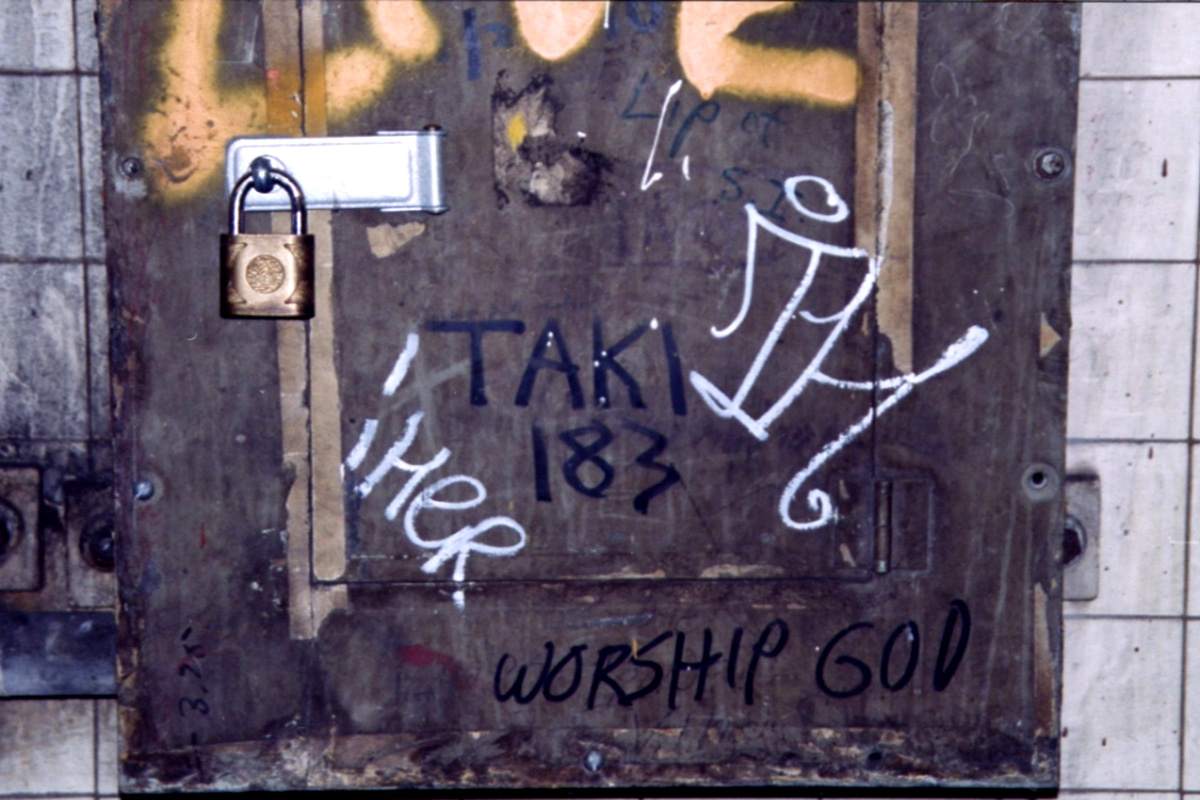

When most people think of graffiti, they imagine "tags," or a stylized writing of a person's name. While tags are probably the most popular forms, graffiti art is much more than that. It can mean a colorful mural with a message of diversity or a black and white stencil piece protesting police brutality. In each case, graffiti art makes a statement.

Creativity

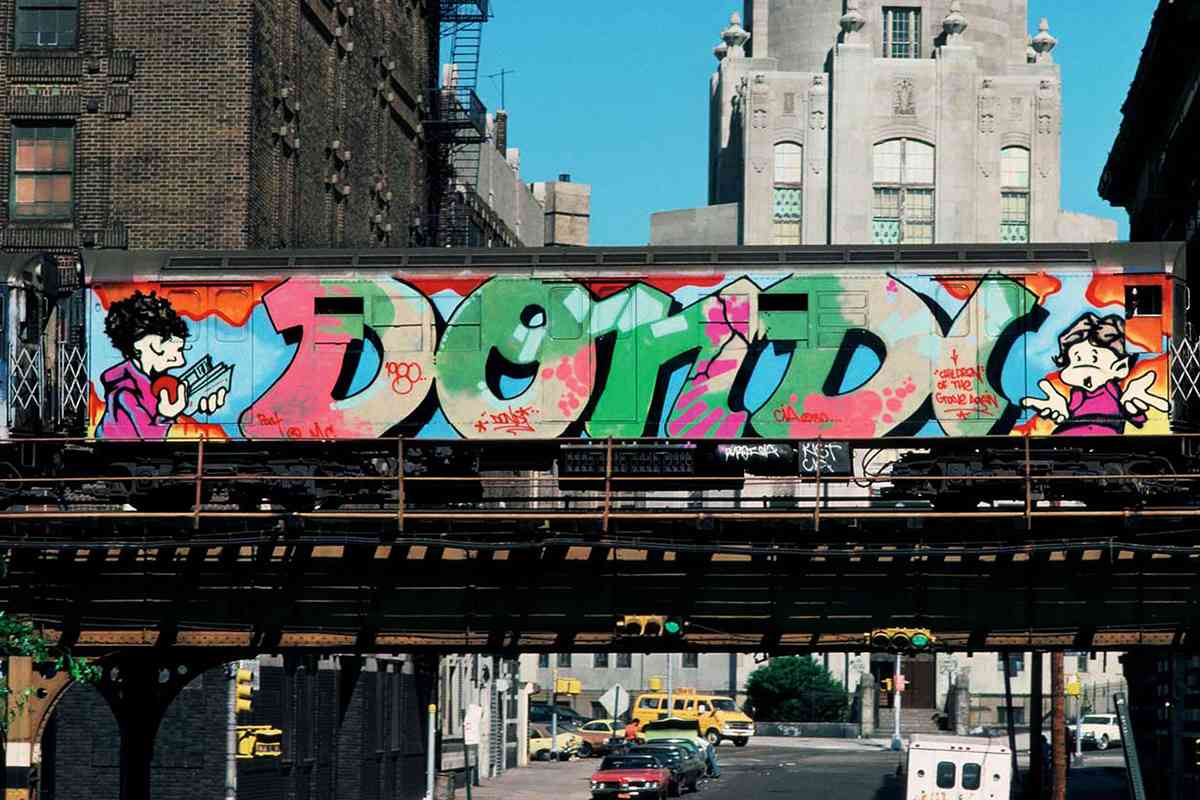

What these kids did, however, was to find a way to express themselves creatively in a society that told them that they didn't have the talent or drive. They came from ghettos that many said were devoid of culture. Graffiti and hip hop in general proved the world wrong. The graf writers (and emcees, and DJs, and bboys) proved that they could create something beautiful that required skill and dedication, something that contributed to the city even if people didn't always understand what it was all about. They expressed their identity in a society that tried to keep them anonymous, that tried to ignore social problems as if they didn't exist. Mayor Ed Koch (in the 1980s) once inquired why the NYC youth couldn't be given brooms and sponges to help the city instead of using their energies to write all over it. Clearly, he didn't understand the difference between being a janitor and being an artist. In our culture, where self-expression is becoming more and more highly regulated, graffiti plays an important role in brashly symbolizing unfettered individuality and resistance.

What these kids did, however, was to find a way to express themselves creatively in a society that told them that they didn't have the talent or drive. They came from ghettos that many said were devoid of culture. Graffiti and hip hop in general proved the world wrong. The graf writers (and emcees, and DJs, and bboys) proved that they could create something beautiful that required skill and dedication, something that contributed to the city even if people didn't always understand what it was all about. They expressed their identity in a society that tried to keep them anonymous, that tried to ignore social problems as if they didn't exist. Mayor Ed Koch (in the 1980s) once inquired why the NYC youth couldn't be given brooms and sponges to help the city instead of using their energies to write all over it. Clearly, he didn't understand the difference between being a janitor and being an artist. In our culture, where self-expression is becoming more and more highly regulated, graffiti plays an important role in brashly symbolizing unfettered individuality and resistance.

Aesthetics

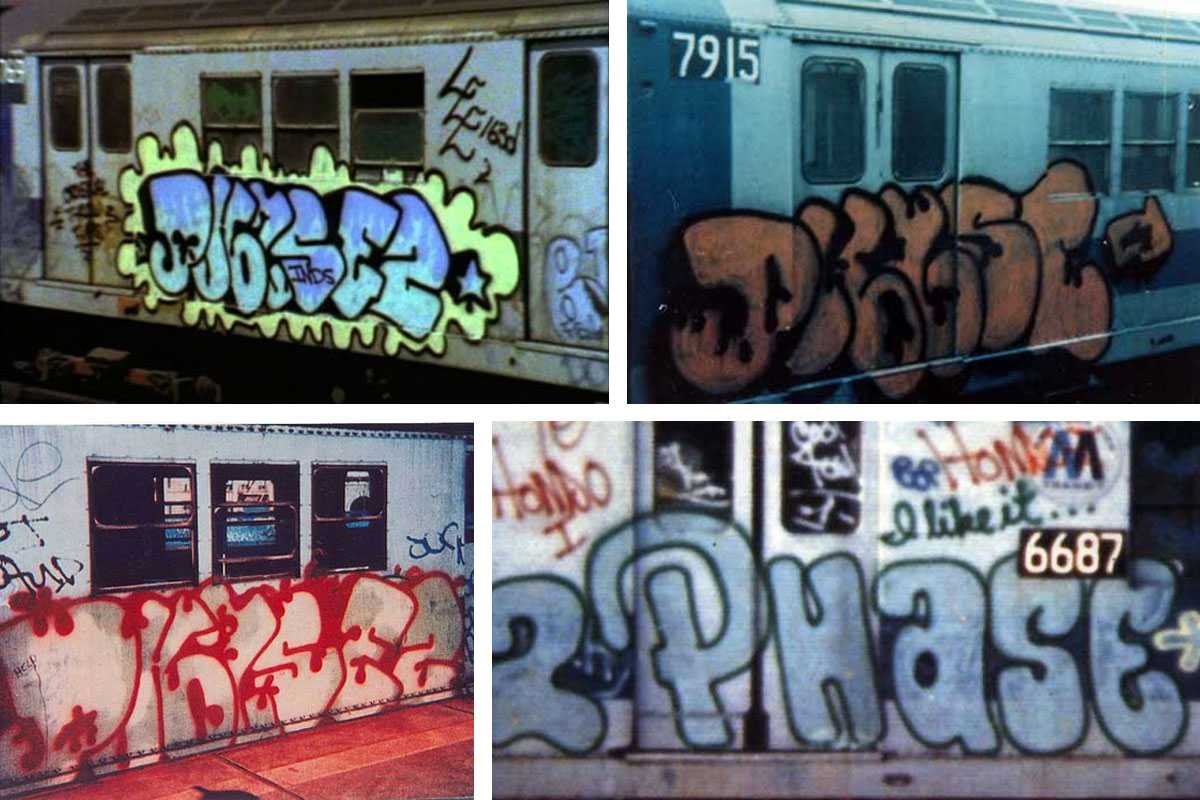

George C. Stowers wrote that based on aesthetic criteria, graffiti has to be considered an art form. He makes a distinction between simple tags and more complicated pieces, stating that tags have little aesthetic appeal and probably should not be considered art. However, larger pieces require planning and imagination and contain artistic elements like color and composition. Stowers provides the example of wildstyle, or the calligraphic writing style of interlocking letters typical of graffiti, to show the extent of artistic elements that are present in these works.

"Wildstyle changes with each artist's interpretation of the alphabet, but it also relies on the use of primary colors, fading, foreground and background, and the like to create these letters," he writes. The artist's intention is to produce a work of art, and that must be taken into account when considering street art's legitimacy.

Stowers explains that graffiti cannot be disregarded because of its location and illegality. The manner in which graffiti art is executed is the only obstacle it faces in being considered an art form.

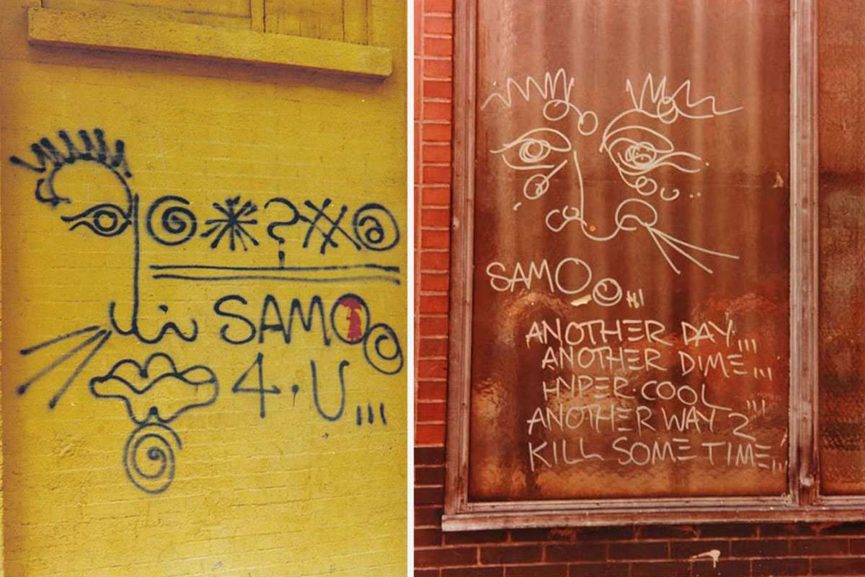

A Nod from the Art Crowd

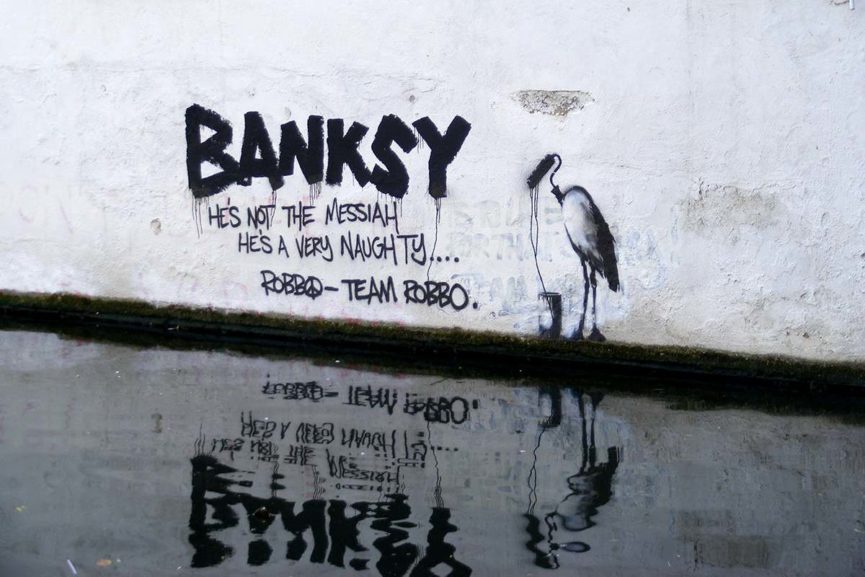

One of the most famous graffiti artists, Banksy, has had his work shown in galleries such as Sotheby's in London. Despite his anonymity, the British artist has gained tremendous popularity. Celebrities such as Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt have purchased his work for a hefty price.People are used to seeing graffiti art in public spaces, after all, that's what makes it graffiti. However, after years of gaining recognition by the art community, graffiti art has been shown in various galleries in New York and London, and artists are often commissioned to do legal murals and other work for art shows.

Recognition by the art world and inclusion in galleries and auctions is one way that graffiti art is legitimized as "real" art. In addition, this exposure has helped the graffiti movement to become launched into the rest of the world.

A Style All Its Own

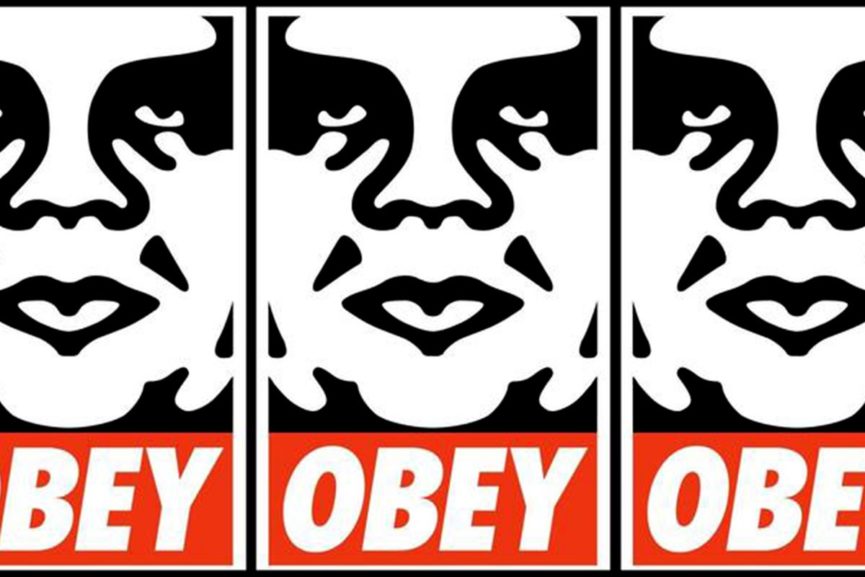

Like all other artistic forms, graffiti has experienced movements or changes in style. From the first tag scribbled on a subway train to the large, complex mural on a billboard, the movement has experienced change. The tools and the means have changed as well. Markers were traded in for spray paint, and stencils and stickers were introduced to make pieces easier to execute in a hurry.

The messages have also evolved. Graffiti has always been somewhat political, but it has come a long way from simply tagging one's name to parodying world leaders to make a statement.

This is further proof that graffiti is a form of art and not just a result of random acts of vandalism. The graffiti community moves in different directions and the resultant artwork moves with it.